Difference between revisions of "What are yeast?"

(→Suggested Reading) |

(→Suggested Reading) |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

York. | York. | ||

| − | Campbell, I., and Duffus, J.H., eds., Yeast (1988) | + | Campbell, I., and Duffus, J.H., eds., Yeast (1988). |

| − | Pfaff, Herman Jan, et al., The Life of Yeasts (1978) | + | Pfaff, Herman Jan, et al., The Life of Yeasts (1978). |

Revision as of 11:42, 16 April 2012

Contents

General Information

Yeast are single-celled eukaryotic microorganisms that are classified, along with molds and mushrooms, as members of the kingdom Fungi. Yeasts are phylogenetically diverse, and as such are classified in two separate phyla, the Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota. Budding yeast (also called “true yeasts”), such as the well-known species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, are classified in the order Saccharomycetales under the phylum Ascomycota. Such classifications are based on characteristics of the cell, ascospore, and colony, as well as on physiology. One of the most well known characteristics of yeast is its ability to ferment sugars for the production of ethanol and carbon dioxide.

Yeast are characterized by a wide dispersion of natural habitats. They are common on plant leaves, flowers, and fruits, as well as in soil. Yeast are also found on the skin surfaces and in the intestinal tracts of

warm-blooded animals, where they may live symbiotically or as parasites. The common "yeast infection" Candidiasis

is typically caused by Candida albicans. In addition to being the causative agent in vaginal yeast infections Candida is also a cause of diaper rash and

thrush of the mouth and throat.

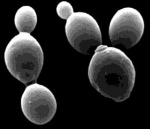

Yeast reproduce asexually by an asymmetric division process called budding (eg. Saccharomyces), by a symmetric division process called fission (eg. Schizosaccharomyces), or they can grow as simple irregular filaments (mycelium). In budding, a small bud emerges from the surface of the parent cell and enlarges until it is almost the size of the parent, while in fission the rod shaped cell grows at the cell's tips and then divides in half to produce two daughter cells of equal size. Yeast can also reproduce sexually, and most do so my forming asci, which contain up to eight haploid ascospores. These ascospores may fuse with adjoining nuclei and multiply through vegetative division or, as with certain yeast, fuse with other ascospores.

Commercial Applications

Saccharomyces cerevisiae are one of the most well-known and commercially significant species of yeast. These organisms have long been utilized to ferment the sugars of rice, wheat, barley, and corn to produce alcoholic beverages, and to expand and raise dough to make bread.

In brewing, Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, named after the Carlsberg Brewery in Copenhagen, where it was first isolated in pure culture by Dr. Emil Christian Hansen (1842-1909) in 1883, is used in the production of several types of beers including lagers. S. carlsbergensis is used for bottom fermentation. S. cerevisiae is used for the production of ales and conducts top fermentation, in which the yeast rise to the surface of the brewing vessel. In modern brewing many of the original top fermentation strains have been modified to be bottom fermenters. Currently the S. carlsbergensis designation is not used, the S. cerevisiae classification is used instead.

The yeast's function in baking is to ferment sugars present in the flour or added to the dough. This fermentation gives off carbon dioxide and ethanol. The carbon dioxide is trapped within tiny bubbles and results in the dough expanding, or rising. Sourdough bread, is not produced with baker's yeast, rather a combination of wild yeast (often Candida milleri) and an acid-generating bacteria (Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis sp. nov). It has been reported that the ratio of wild yeast to bacteria in San Francisco sourdough cultures is about 1:100. The C. milleri strengthens the gluten and the L. sanfrancisco ferments the maltose.

The fermentation of wine is initiated by naturally occurring yeast present in the vineyards. Many wineries still use natural strains, however many use modern methods of strain maintenance and isolation. The bubbles in sparkling wines is trapped carbon dioxide, the result of yeast fermenting sugars in the grape juice. One yeast cell can ferment approximately its own weight of glucose per hour. Under optimal conditions S. cerevisiae can produce up to 18 percent, by volume, ethanol with 15 to 16 percent being the norm. The sulfur dioxide present in commercially produced wine is actually added just after the grapes are crushed to kill the naturally present bacteria, mold, and yeast.

In addition to playing a major role in baking, brewing, and wine making, the in-depth knowledge of S. cerevisiae and it's ability to be metabolically engineered has made it an important organism in the production of specialty chemicals, such as biofuels, industrial lubricants, detergents, and biopharmaceuticals.

Yeast as a Model Organism

Yeast, particularly S. cerevisiae, became a model organism for studying cell biology and genetics because it is a single-celled eukaryote that is fairly easy to manipulate and grow, and the basic cellular mechanics of replication, recombination, cell division and metabolism are generally conserved between it and more complex eukaryotes, including humans. As a result it is one of the most thoroughly researched eukaryotic organisms. Several significant scientific discoveries have been made by studying S. cerevisiae.

The Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) provides comprehensive integrated biological information for the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae along with search and analysis tools to explore these data.

Suggested Reading

The Early Days of Yeast Genetics. (1993) edited by Michael N. Hall and Patrick Linder. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Gene Expression. (1992) edited by Elizabeth W. Jones, John R. Pringle, and James R. Broach. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

Mortimer, R.K., Contopoulou, C.R. and J.S. King (1992) Genetic and physical maps of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Edition 11. Yeast 8:817-902.

The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Genome Dynamics, Protein Synthesis, and Energetics. (1991) edited by James R. Broach, John R. Pringle, and Elizabeth W. Jones. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

Campbell, I., and Duffus, J.H., eds., Yeast (1988).

Pfaff, Herman Jan, et al., The Life of Yeasts (1978).